The Paradox of Rubric-Based Writing

What a boring title…rubric-based writing…I am sure this would be a big seller on Amazon: “Buy Now and Save on Fitz’s Narrative Paragraph Rubric!” Frustration guaranteed! Used by hundreds of angry students…

What a boring title…rubric-based writing…I am sure this would be a big seller on Amazon: “Buy Now and Save on Fitz’s Narrative Paragraph Rubric!” Frustration guaranteed! Used by hundreds of angry students…

To Create Effective Transitions in Essay Writing

The Power of a Natural and Logical Flow

The crazy thing about transitions is that we are already masters of transitions. All of us have been practicing and perfecting a natural and logical flow for as long as we have been speaking. So whats the big deal when trying to employ effective transitions in our writing?

In all of my years of teaching and writing, no one has really defined what a paragraph is that has left me feeling like “Whoa, now I know!” When I write, I create new paragraph whenever it “feels” like a paragraph is needed. Where and how that “feeling” happens is the fodder for debate.

For the most part, my shifts are pretty much in line with accepted paragraph usage. I transition to a new paragraph when my thoughts shift in a new direction or there is a change—often even a very slight change—in mood and tone. Sometimes, I’ll even just hang a sentence out in space to give the reader a break or a pause for thought, but never as a break or pause for the writer, which would be like stopping in the middle of a conversation just because you want to rest.

As humans we have a great intuitive sense for how to complete a thought, how to move to a new thought, and how to end a conversation with some degree of grade and normality. A good writer develops the confidence to trust that intuition; a bad teacher hyper-analyzes it.

The annoying thing is that most of us have been taught (usually by that hyper analyzing teacher) that transitions are some kind of visible and mechanical bridge, and without the bricks and mortar of that bridge an essay will fall to pieces and crumble into a disarray of babbled words and incoherency.

Not true! An essay falls apart when the unifying theme of the essay becomes unglued or weighted down by too much extraneous stuff—stuff that does nothing to further your essay, stuff that makes a reader say, “I have no idea what you are trying to say!”

Simply put: know your topic and stick to it. Everything else will fall into place.

There is an Irish story of twin brothers, one who was very studious and the other not studious at all. Their assignment in English was to write an essay about a pet. After the papers were graded, the teacher called the less studious brother aside and said in a chiding way: “ Your essay about your pet dog was exactly the same as your brother’s essay.” To which the he responded, “What did you expect? It’s the same damn dog.”

The point of that story? If the reader knows what you are writing about, and you stay more or less focused on that topic (or topics) your reader will not be confused by how you structure your paragraphs or craft your transitions between paragraphs. If it reads like a conversation from your head and heart, no lasting damage has been done to the fabric of the universe.

But it still might be a lousy essay. And maybe it is lousy because of the way you transitioned (or more than likely did not transition) between paragraphs. Maybe your essay resembles more of a trip down a mountain ski slope in an old VW Beetle with your little brother punching you in the arm and yelling “Punch Buggy” the whole way down the hill.

The bottom line is that an essay needs—as in really needs—a natural and confident flow. A reader needs to feel that the writer is in control from start to finish, and anything that interrupts that flow is more annoying than it is engaging; otherwise, your essay is doomed to that anonymous dropbox in the cloud where most essays go when they die.

So make your essay live. Don’t just write—breathe! Make your essays as alive as you are. Be real and write about what you know, and if you don’t know, don’t fake it—learn what you need to know, and then start writing. And opposed to what many teachers teach, use the voice that is most alive in your head—even if it is the dreaded “I” voice. It is, after all, you who are writing. Be real. Avoid words you don’t already know and use. You don’t want to be one of those “phoneys” that Holden Caulfield singles out in Catcher in the Rye. Be real because you really are real and no one is better than you at being you.

So easy for a wordy English teacher to preach, and I am not the one writing the essay (Oh my god, he used the I voice in an essay!) and you are not the one who assigned the writing prompt, but like Odysseus sailing into the Straits of Skylla, the only way out is through, so write you must.

My long-winded preamble is over, and now I will give you a few tricks to help you create transitions in a traditional five-paragraph essay or any kind of formal essay that might be graded in a traditional and rigorous way by the mighty red pen of academia.

Technique #1:

Connecting Thoughts

SOYET ANDOR NORFORBUT

My little acronym is meant to sound like a Russian spaceship, but it is merely a disguise for the all of the hidden coordinating conjunctions—those cool little words that connect independent clauses to create longer compound sentences, and which tie together two or more “related” thoughts.

That’s the main point: “two or more related thoughts.”

Now here is my little trick: “If” you could (thought you won’t actually do it) add a conjunction to the end of one paragraph and lead into the opening line of the next paragraph you have created a logical transition—a bridge between paragraphs that a reader can cross to your new thought without falling into the roiling water of confusion.

For Example:

Huck Finn escapes society by escaping from his abusive father, but Jim seeks freedom from slavery for himself and his family.

The transition sentence at the end of the paragraph is:

Huck Finn escapes society by escaping from his abusive father.

The topic sentence or narrow theme of the next paragraph is:

Jim seeks freedom from slavery for himself and his family.

Technique #2:

Stealing and Thievery

Technique number two uses the coordinating conjunction trick and takes it one step further.

Steal a theme, a topic, an idea—or even just a word—from one body paragraph and use it to start your next paragraph.

For Example:

The cunning deceits of Odysseus help him overcome the trials he faces while trapped in the Cyclop’s cave, [but] without bravery, Odysseus could never pull off his cunning plans.

The transition sentence at the end of the paragraph is:

The cunning deceits of Odysseus help him overcome the trials he faces while trapped in the Cyclop’s cave.

The topic sentence or narrow theme of the next paragraph is:

Without bravery, Odysseus could never pull off his cunning plans.

Technique #3:

The Conjunctive Adverb Trick

Like a coordinating conjunction, conjunctive adverbs connect two or more related independent clauses—but even better, conjunctive adverbs show the relationship between those independent clauses.

Conjunctive adverbs are words and/or phrases like:

accordingly, furthermore, moreover, similarly,

also, hence, namely, still,

anyway, however, nevertheless, then,

besides, incidentally, next, thereafter,

certainly, indeed, nonetheless, therefore,

consequently, instead, now, thus,

finally, likewise, otherwise, undoubtedly,

further, meanwhile, in spite of, on the other hand,

in contrast, on the contrary, ETC…

In the same way as techniques one and two, “if” you could put a conjunctive adverb at the end of a body paragraph and lead into the first sentence of the next paragraph, you have an effective transition—as long as you are using the conjunctive adverb correctly.

For Example:

In Walden, Thoreau urges us to live more simply and thoughtfully; moreover, Thoreau gives an example of his own life and his own idea of simplicity and thoughtfulness through his experiment on Walden Pond.

The transition sentence at the end of one body paragraph is:

In “Walden,” Thoreau urges us to live more simply and thoughtfully.

The opening sentence of the next paragraph is:

Thoreau gives an example of his own life and his own idea of simplicity and thoughtfulness through his experiment on Walden Pond.

Technique #4:

The Dangling Paragraph

This technique can save an essay from itself. Oftentimes, we have a paragraph or thought that is hard to connect to the next paragraph. The dangling paragraph comes to the rescue.

A dangling paragraph is a paragraph that is very brief compared to the body paragraphs it is sandwiched between. It’s effect on the reader is meant to be clear, concise and compelling—and even startling. It can be a statement, a question, or just a philosophical pondering.

For Example:

Because I can imagine myself sailing in a twilight breeze across Pleasant Bay, I will put up with these days of gluing, screwing and painting, varnishing and rigging my old sailboat. Sometimes I wish I had the money to just buy a boat that doesn’t need so much of my time, but like anything else in life that steals my time, I must figure it’s worth it—and it is. I do other things with my time where I don’t have the same clarity of purpose. It is a rare moment of quiet in my house; the kids are all off with Denise somewhere, and though the grass is absurdly high; the van desperately needs an oil change, and the gutter is hanging by a twisted coat hanger, I sit here and force a few words out of emptiness. A part of me wants to show the folks in my writing communities that I practice what I endlessly preach to them—face the empty page! But it’s not that simple; I’ve been doing the same thing for almost thirty years, seldom with any goal but the action of writing itself.

Is it worth it? [This is the dangling paragraph!]

Everything that I write returns to me obliquely. I’ve never written for a publication; I’ve never even tried to get anything published, save for a small book of poetry and a couple of CD’s. I’m a whiz when it comes to writing recommendations, and I can write a decent song or poem for any occasion, but I still can’t say that I write out of a labor of love or because I have some over-arching goal. I write because it gives purpose and meaning and clarity to my life. It stills me when I need to be still, and it roils me out of my ignorant slumber when I need to wake and see the light of day. Used wisely, writing humbles my arrogance and helps me open my arms and doors when I might otherwise retreat into a self satisfied shell of complacency. It is worth a long day on the water to be there when the wind and tide help beat the way to a new harbor.

My goal with my short dangling paragraph was to shift my topic and to get my readers to ask the question with me. It’s purpose is to get the reader to stop, read, rethink and shift gears—as in to redirect the topic of the next paragraph. It allows a writer to avoid an otherwise messy transition and move his or her essay in a new direction.

Make sense to you?

That last paragraph is an example of another dangling paragraph! Used with care and discretion, it is an effective technique.

Used as a habit, it will soon become a bad habit.

Both 8th grade and 9th grade are working on opening paragraphs, and I bet more than a few of you are a bit stumped on how to start. Some of you may even be working on a conclusion.

Wouldn’t that be nice.

My best advice is to use the latest version of my iBook “Fitz’s Literary Analysis Rubric.” The latest version is in the Materials section of your course on iTunes U. If you do not have the latest version, simply delete your version in iBooks and upload the new version.

You can also go to the Opening Paragraphs site on my Resources and Rubrics Page, which has essentially the same information as in my iBook.

Here is a good opening paragraph for The Odyssey already turned in by Ahbinav Tadikonda. It might give you an idea of what might work for you–in your own words and ideas!

Everyday is the same: Odysseus travels the vast seas with his crew in hope to return home only to be disappointed day after day. Enduring the pain of a thousand men Odysseus keeps moving on, being the hero he is. But what is a hero anyways? When most people think of a hero, they think of a tall, muscular, and handsome being that could do no wrong; however, Odysseus is not all that perfect. Odysseus, is often rude, disrespectful, and not always the most attractive male. However he is still a hero. He shows he is a hero by the way he handles difficult times. For Odysseus disaster as constant as the sun rising everyday. Even getting out of bed has become dangerous for him. From battling cyclops’s to being away from family for over 17 years, it really makes you ask: how is it that through all the terrible times Odysseus still shows his maturity, bravery and courage?

For you ninth graders, check out this opening written by Mike Demsher a couple of years ago:

Throughout human history, we have advanced. Whether it is electronically, medically or socially, we have moved forward to a better society; however, could we be moving in the wrong direction? We have advanced our lives to a point where we are constantly hurrying with everything we do. We have been moving into a world where there is no real thought. We are in a philosophical dark age. The only way to snap ourselves out of it is to slow down and think. We must live deliberately each day and remember who we are meant to be. In Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, Thoreau urges us to live our lives purposefully and to not give up who we are. He wants us to live with our eyes open and not to fall into the blur that society is moving towards. Henry David Thoreau wants us to live deliberately.

Done with all that…?

If you are working on your conclusion, go to my “Essay Conclusions” website and see the rubric there, which is geared towards concluding a literary anlaysis essay.

Please steal my rubric from me!

For the ninth graders writing an essay on Walden, the example essay on my “How to Write Literary Essays” site uses a Walden essay ( and a fine one) as an example of how to put together an entire essay.

It’s a big project, and I am really only hoping that your write carefully and use the rubrics carefully. If you do, you will do well.

I hope this helps!

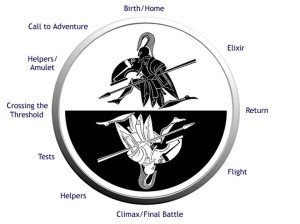

The hero cycle is not a rubric created for storytellers; it is the primal urge of all people—across ALL cultures—to experience within their own lives the transformation of being a hero. Every ancient culture that has had its history recorded has some epic poem or story to guide its people. The heroic cycle represents the power of hope over despair; it gives us all the chance for redemption—even in the hardest of times. It is a recognition that without agnos (pain) there is no aristos (glory), and, in that sense, it validates even the most common and hard-bitten of lives by making the lives of every man, woman and child that has ever lived uncommon, unique, and worthwhile.

The hero cycle is not a rubric created for storytellers; it is the primal urge of all people—across ALL cultures—to experience within their own lives the transformation of being a hero. Every ancient culture that has had its history recorded has some epic poem or story to guide its people. The heroic cycle represents the power of hope over despair; it gives us all the chance for redemption—even in the hardest of times. It is a recognition that without agnos (pain) there is no aristos (glory), and, in that sense, it validates even the most common and hard-bitten of lives by making the lives of every man, woman and child that has ever lived uncommon, unique, and worthwhile.

It is not an absurd idea to recognize the greatness and possibilities of our own lives. It is not absurd to think we have an epic tale worth telling, and it is certainly not absurd to examine every experience through a reflective lens and to start to appreciate the implications of transformation which heroic poetry represents. As human beings, we are hard-wired to need this epic poetry. We can’t just read the epic as a story and move on. We have to know the story and build and incorporate the allegory into our own lives; otherwise, we will run from the battles of life; we will avoid the straits of Skylla and the lair of the Cyclops; we will shun the Gods who come disguised to us and coddle the children given to us; we won’t shed tears for common friends, and we will lock out every stranger and blame our mishaps and misdeeds on the gods.

In short, we will not be remembered, and no songs will be sung about us. The saddest part is that you may think this is all exaggeration and hyperbole. But, it is not! Our lives are full of stories that use and embody the heroic cycle. In fact, I have a hard time trying to think of any “great” movie, book, or story that in same way, shape or fashion

Try to come up with a book or movie that you feel is a meaningful and powerful story that follows this heroic cycle. Fill in the blank boxes with a brief description of the scenes that best illustrate the use of the hero cycle in the story.

The assignment will be posted on iTunes U. If you have any problems, you can use this rubric. Open it in Pages.

Download the rubric:

Upload the Fitz Style Journal Entry Rubric

How To Create a Fitz Style Journal Entry

Set the Scene & State the Theme; Say what you mean, and finsih it clean

When writing a blog post, is important to remember that a reader is also a viewer. He or she will first “see” what is on the screen, and that first impression will either attract their attention and interest—or it may work to lose their attention and interest; hence, a bit of “your attention” to the details will go a long way towards building and maintaining an audience for your work. Plus, it gives your blog a more refined and professional look and feel—and right now, even as a young teenager, you are no less a writer than any author out there.

So act like a writer. Give a damn about how you create and share your work and people will give a damn about what you create! It is a pretty simple formula.

The “Fitz Style” journal entry is one way to do it well! I call it “Fitz Style” only because I realized that over time my journal posts began to take on a “form” that works for me. Try it and see if it works for you. You can certainly go above and beyond what this does and add video or a podcast to go along with it—and certainly more images if it is what your post needs. Ultimately, your blog is your portfolio that should reflect the best of who you are and what interests you at this point in your life presented in a way that is compelling, interesting, and worth sharing.

One of the hardest parts of writing is finding a way to make sense of what you want to say, explain, or convey to your readers–especially when facing an empty page with a half an hour to kill and an entry to write (or a timed essay or exam writing prompt). The Fitz Style Entry is a quick formula that might help you when you need to create a writing piece “on the fly.” At the very least, it should guide you as your write in your blog, and at the really very least, it will reinforce that any essay needs to be at least three paragraphs long! I’ve always told my students (who are probably tired of hearing me recite the same things over and over again): “If you know the rules, you can break them.” But you’d better be a pretty solid writer before you start creating your own rules. The bottom line is that nobody really cares about what you write; they care about how your writing affects and transforms them intellectually and emotionally as individuals.

If a reader does not sense early on that your writing piece is worth reading, they won’t read it, unless they have to (like your teachers), or they are willing to (because they are your friend). Do them all a favor and follow these guidelines and everyone will be happy and rewarded. Really!

Formatting

How something “looks” is important. Never publish something without “looking” to see the finished product in your portfolio or blog.

Interesting Title

After the initial look, the title is the first thing a reader will see. The title should capture the general theme of your journal entry in an interesting and compelling way.

Interesting Title

After the initial look, the title is the first thing a reader will see. The title should capture the general theme of your journal entry in an interesting and compelling way.

Eye-catching Image

An image embedded in your post is the final touch of the formatting. A picture really does paint a thousand words and this final touch prepares your readers and entices them to read the important stuff—the actual writing piece you create.

Opening Paragraph

The “Hook!”

A hook is just what it says it is—a way to hook your reader’s attention and make him or her eagerly anticipate the next sentence, and really, that is the only true hallmark of a great writer!

Set the Scene

Use your first paragraph to lead up to your theme. If the lead in to your essay is dull and uninspired, you will lose your readers before they get to the theme. If you simply state your theme right off the bat, you will only attract the readers who are “already” interested in your topic. Your theme is the main point, idea, thought, or experience you want your writing piece to convey to your audience. (Often it is called a “Thesis Statement.)

State the Theme

I suggest making your theme be the last sentence of your opening paragraph because it makes sense to put it there, and so it will guide your reader in a clear and, hopefully, compelling way. In fact, constantly remind yourself to make your theme be clear, concise and memorable. Consciously or unconsciously, your readers constantly refer back to your theme as mnemonic guide for “why” you are writing your essay in the first place! Every writing piece is a journey of discovery, but do everything you possibly can to make the journey worthwhile from the start.

Body Paragraphs

Say What You Mean

Write about your theme. Use as many paragraphs as you “need.” A paragraph should be as short as it can be and as long as it has to be. Make the first sentence(s) “be” what the whole paragraph is going to be about.

Try and make those sentences be clear, concise and memorable (just like your theme) and make sure everything relates closely to the theme you so clearly expressed in your first paragraph. If your paragraph does not relate to your theme, it would be like opening up the directions for a fire extinguisher and finding directions for baking chocolate chip cookies instead!

And finally, do your best to balance the size of your body paragraphs. If they are out of proportion to each other, then an astute reader will make the assumption that some of your points are way better than your other points, and so the seed of cynicism will be sown before your reader even begins the journey

Conclusion

Finish It Clean

Conclusions should be as simple and refreshing as possible. In conversations only boring or self important people drag out the end of a conversation.

When you are finished saying what you wanted to say, exit confidently and cleanly. DON”T add any new information into the last paragraph; DON’T retell what you’ve already told, and DON’T preen before the mirror of your brilliance. Just “get out of Dodge” in an interesting and thoughtful (and quick) way.

Use three sentences or less. It shows your audience that you appreciate their intelligence and literacy by not repeating what you have already presented!

Now give it a try!!!

Recent Comments